Internal mini form

Contact Us Today

Cyclist, Paralympian

and Advocate

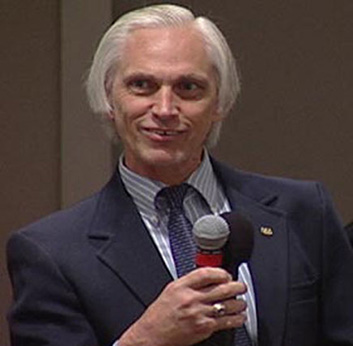

Duncan Wyeth, 66, used his bike not only to become an elite athlete, but an example to disabled athletes on domestic and foreign shores.

As a child, Duncan was gifted a bike even though he wore leg braces. Finding it physically easier to ride the bicycle than run or walk, the bike empowered him to play alongside and socialize with other children. “I was proud of my ability to ride the bike,” Duncan said, even though he had to use training wheels for a longer duration than most children require. “A lifelong cyclist was born.” Duncan is an accomplished athlete, Paralympian and disability advocate. He devotes his energies towards the promotion of health, wellness, athletics and education to those with disabilities.

Cyclist, Paralympian uses sport to reach new heights

There’s a scene in the 1994 movie “Forrest Gump” that shows Forrest as a small boy, hamstrung by leg braces, walking along a dirt path with his friend when, all of the sudden, he is pursued by bullies on bicycles.

As Forrest attempts to elude the boys, his braces, piece by piece, fall to the wayside, and the hero is off and running.

And although Duncan Wyeth, a 66-year-old bicyclist and Paralympian with spastic Cerebral Palsy, doesn’t remember his leg braces coming off in quite the same way, the image, for him, is both powerful and cathartic.

“I had leg braces growing up,” said Duncan, who lives in the town of Holt, Mich., which is located near Lansing, the state’s capital. “It made life difficult mostly because it made me different, but I never let it get me down.”

Even though it may not have been conceivable in the late 1950s, Duncan’s destiny would not be held back by braces. Duncan’s first bike, which he received when he was about 7 years old, would be life changing.

The path Duncan has traveled – on and off his bike – has taken him from riding along small paths with local cycling groups to the ultimate world’s competitive stage. By 1982, Duncan would be the first American to win a medal as a member of the U.S. Cerebral Palsy Games team; the games were held in Copenhagen, Denmark. The Cerebral Palsy Games were organized by the Cerebral Palsy International Sports and Recreation Association. The national and international versions of these games would eventually fall to the wayside as organized disability sports evolved to look more like conventional professional competitions, said Duncan.

“When I was growing up, I believed that I could do the same things other people my age did. But I knew there would be times when I would have to do those things differently.”

– Duncan Wyeth

Six years after his victory at the Cerebral Palsy Games, Duncan found himself on the world stage in Seoul, Korea, competing with other elite athletes at the 1988 Paralympic Games.

A diagnosis for success

Duncan was born in 1946, which was a time when physicians did not know as much about Cerebral Palsy or its causes as they do today. Diagnosed as an infant after his parents, a college administrator named Irving and housewife Barbara, noticed he was not meeting developmental milestones as their other children had, physicians told the Wyeths they needed to place Duncan in an institution.

That suggestion was immediately rebuffed, Wyeth said.

“The first lesson I learned was to choose your parents carefully,” Duncan said. “My father especially did not believe that was the right thing to do, and I was held to the same standards as my siblings.”

When Duncan was in the third grade, he helped his father landscape his family’s front lawn to earn money for a bicycle. At the end of the summer, Duncan was the proud owner of a bike with training wheels, which he initially used to learn how to balance on the bike.

“The first lesson I learned was to choose your parents carefully. I was held to the same standards as my siblings.”

– Duncan Wyeth

When Duncan received his first bicycle, he was still wearing braces. But, he found it physically easier to ride the bicycle than to run or walk. The bike also engendered a sense of empowerment in Duncan.

“I remember that for me to be able to keep up with other children in the neighborhood, I needed the bike, even if it did have training wheels,” he said. “I was proud of my ability to ride the bike. A lifelong cyclist was born.”

Duncan spent the next several years riding his bike, and becoming a high achiever in school, which he said was in large part because of his parents’ belief that he could achieve in the same manner as Duncan’s father and siblings, all of whom attended college. In 1964, he entered Alma College in Alma, Mich., before transferring to Michigan State University in East Lansing, where he earned a bachelors’ and master’s degrees in education and social sciences. He began teaching in the Lansing Catholic School system.

“When I was growing up, I believed that I could do the same things other people my age did,” Duncan said. “But I knew there would be times when I would have to do those things differently.”

The national spotlight;

an opportunity of a lifetime

Duncan was in his late 20s when he began taking part in athletic competition. In 1981, Duncan clinched 14 gold medals at the Michigan Regional Cerebral Palsy Games, and two golds and a silver at the National Cerebral Palsy Games. At the 1982 World Cerebral Palsy Games, he brought home a bronze in a cycling event, and a silver in the discus.

But in 1988, when he was 32 years old, an opportunity to compete on a stage unlike any other came to fruition.

The Paralympic Games were commencing in Seoul, Korea; the same city that hosted the Summer Olympics months earlier. At the time Duncan was competing professionally, his performance at competitions stateside allowed him to qualify for the U.S. cycling team. Today, qualifications have been adapted to coincide with Olympic standards and incorporate Paralympic trials.

“The Paralympics was a wonderful experience for me,” he said. “It was the culmination of a lifetime of effort. And because the 1988 was the first time the Paralympics and Olympics were held in the same city, we worked out and competed in the same state-of-the-art facilities as the Olympic athletes.”

At the Paralympics, Duncan placed fifth among 40 cyclists in the 30-kilometer road race. He said the fact that he did not come home with a medal did not diminish his experience because he was with other athletes, all of whom defied the odds to compete on the world stage.

Though his competitive cycling days were over, Duncan returned to the Paralympics’ 1992 Barcelona Games as an administrator for the U.S. team. At the 1996 Atlanta Games, he served as the Chef De Mission.

“The Chef de Mission is a fancy French way of saying I was the head of the U.S. delegation,” he said. “It meant that I got to give the team jacket to Vice President Al Gore. It was a huge honor.”

Duncan returned to the Paralympics for a final time in 1998, where he served as an officer for the Winter Games in Nagano, Japan.

Recognition and perspective

Duncan’s achievements in the athletic arena have not gone unnoticed; he has won several awards and honors as an athlete.

In 1988 – the year he competed as a Paralympian – he was named Male Athlete of the Year by the United States Olympic Committee, and the Cerebral Palsy Male Athlete of the Year by the Colorado Amateur Sports Corp.

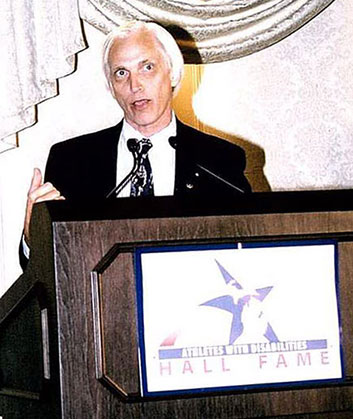

Duncan was inducted into the Michigan Athletes with Disabilities Hall of Fame in 2000 for his achievements in cycling, and again in 2004, when he was awarded the Rick Knas Lifetime Achievement Award, which is given to athletes for athletic achievement, taking an active role in supporting athletic programs, and advocating for athletic participation in the disabled community.

In 2000, the American Academy on Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine introduced the Duncan Wyeth Award to recognize individuals that contribute to the health of persons with disabilities by using sports and recreation.

Duncan has also been extensively published both locally and nationally. His writing has appeared in medical journals such as “Sports and Exercise for Children with Chronic Health Conditions,” and the “Journal of Osteopathic Sports Medicine.”

Additionally, he contributed to a book about sports and disability called “Go For It,” and wrote a guest column on the same subject for USA Today.

Education makes a difference

Duncan said that two factors made a difference in his life – education and athletics. He credits his parents for creating an environment that allowed him to explore his athletic abilities, while demanding he achieve academically.

“Early on I understood that I would attend college,” he said. “I have both master’s and bachelor’s degrees, and that has helped me work full-time and live independently.”

Professionally, Duncan recently retired as the executive director of the Michigan Commission on Disability Concerns, which is a state agency that makes policy recommendations to lawmakers regarding issues that affect the disabled community. He is also an adjunct faculty member at Michigan State University, in East Lansing, Mich., where he teaches a course called “Disability in a Diverse Society.”

Duncan’s advice for parents is to stress abilities, not disabilities. He said that if not for cycling, he would likely be in a compromised physical state today.

Still an avid cyclist, Duncan has never added any adaptive equipment to his bicycle. But, he’s considering converting to a trike, which has additional wheels, mostly because of his advanced age, not because of his physical condition.

“I have no doubt that someone in my condition would be in a wheelchair if not for the cycling,” he said. “But now, I’m older, and I would like the added security. But I know I will ride a bicycle for the foreseeable future.”

Athletic Achievements

1981 – 14 Gold Medals, Michigan Regional Cerebral Palsy Games

1981 – 2 Gold and 1 Silver, National Cerebral Palsy Games

1982 – Silver Medal (Discus) Bronze Medal (Cycling), World Cerebral Palsy Games, Coppenhagen, Denmark

1986 – Presidents Award, UCPA of Michigan

1988 – Male Athlete of the Year, U.S. Olympic Committee

1988 – Cerebral Palsy male Athlete of the Year, Colorado Amateur Sports Corp.

1988 – Fifth Place, Cycling Paralympian, U.S. Team, 1988 Paralympic Games, Seoul, Korea

1992 – Administrator of the U.S. Team, 1992 Paralympic Games, Barcelona, Spain

1996 – Chef de Mission (Head of U.S. Delegation), 1996 Paralympic Games, Atlanta, Georgia

1998 – Officer for the International Paralympic Committee, 1998 Winter Games, Nagano, Japan

2000 – The American Academy on Cerebral Palsy and Developmental Medicine established the “Duncan Wyeth Award” to honor an individual who significantly contributes to the health and wellness of persons with disability through sports and recreation.

2001 – Inducted into the Michigan Athletes with Disabilities Hall of Fame

Professional Achievements

and Accomplishments

Retired Executive Director, Michigan Commission on Disability Concerns

Adjunct Faculty Member, Michigan State University, East Lansing, Mich.

Teacher and Administrator, Lansing Catholic School Systems, Lansing, Mich.

1866 – President’s Award, UCPA of Michigan

1994 – Outstanding Alumnus, Michigan State University

1998 – National Leadership Award, National Council on Disability

2004 – The Rick Knas Lifetime Achievement Award

Athletes with Cerebral Palsy

Athletes are mythic figures that have used their bodies to achieve an enviable level of fitness. Although most people don’t associate individuals with Cerebral Palsy with sports and other acts of endurance, these athletes use their bodies to achieve feats of physicality that are only surpassed by personal satisfaction and confidence.

- Sam Broughton – Martial Arts

- Drew Dees – Shot Put

- James “Rooster” Gallion – Parkour

- Dick and Rick Hoyt – Triathletes

- Benjamin Jackson – High School Sports

- Cody and Cayden Long – Triathletes

- Linda Mastandrea – Paralympian

- Ryan McGraw – Yoga

- Kyle and Brent Pease – Triathletes

- John Quinn – Navy

- Jack Runser – Wrestler and Bodybuilder

- Jerry Traylor – Mountain Climber

- Marty Turcios – Golfer

- Ahkeel Whitehead – Paralympic Hopeful

- Duncan Wyeth – Paralympian