Internal mini form

Contact Us Today

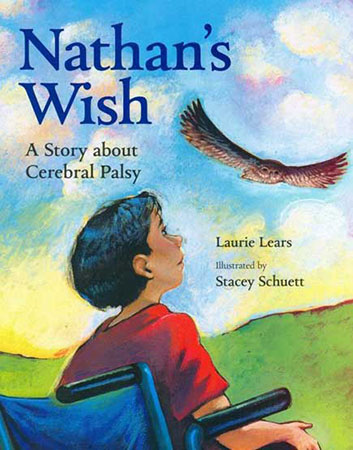

‘Nathan’s Wish’ focuses on abilities, not disabilities

Nathan is a boy that could live in any neighborhood, large or small, as long as that community has a kind raptor rehabilitator and a determined screeching owl.

And so begins “Nathan’s Wish” (Albert Whitman & Co., 2005), a 30-page children’s book written by Laurie Lears.

The book, which is geared towards young children, was specifically designed to teach youngsters life lessons about disability by way of an engaging plot. “Nathan’s Wish” uses allegory in the form of a wounded owl to show children that despite the fact that some bodies may work differently, everyone has the same desires for friendship.

The main character lives with his family and enjoys the things that other children enjoy, like animals and computers.

Early on Nathan begins to notice his differences and laments his physical limitations. He experiences a crisis of confidence due to the fact that his Cerebral Palsy means he must use his wheelchair or walker to get to and from school, and the home of his friendly neighbor Miss Sandy who happens to rehabilitate injured birds.

“More than anything, I wish I could walk by myself,” he said. “Then I would help Miss Sandy with her chores instead of just watching her. But I have Cerebral Palsy, and my muscles don’t work well enough for me to get around without my wheelchair or walker.”

“Every day I watch Miss Sandy mix medicines, give out food, and clean the big cages in her backyard,” Nathan said. “No matter how tired or busy she is, Miss Sandy always takes time to talk to me about the birds.

One day, Miss Sandy shows Nathan an owl with a broken wing that she is rehabilitating. The owl’s name is Fire because of her bright, engaging eyes. Nathan can see the owl is experiencing anger because she cannot fly.

Fire struggles each day to regain the use of her wing. Although Nathan worries that the injured owl will hurt herself once again, he notices that each day Fire gets a little stronger. Eventually, Fire is moved to a bigger cage to allow her to use her wings more frequently; Nathan secretly hopes that if Fire can fly like other owls, maybe he will one day walk like other little boys.

“How much longer will she have to stay?” Nathan asks Miss Sandy.

“A broken wing takes a long time to get strong again,” Miss Sandy said. “I believe you are as impatient as Fire, Nathan.”

As Nathan becomes consumed by Fire’s predicament, Miss Sandy decides to see if Fire can fly.

At first, Fire soars. But then she falls to bottom of a flight cage, and at that point, Nathan and Miss Sandy realize she can never be released into the wild.

“I turn away so Miss Sandy won’t see the tears slipping down my cheeks,” Nathan said. “I know just how it feels to wish for something that can’t come true.”

Nathan watches as the light goes out of Fire’s eyes. He wonders what he, a boy that cannot walk on his own, can do to help Fire who remains still on a perch.

Nathan does some research, and finds a fix to bring contentment to the owl he has come to love so much. And soon, Fire is happy – even though that fix doesn’t include flying again.

Nathan’s wish outlines a lesson that children with – and without – disabilities can learn from. Everyone, no matter what their physical condition, can find something they love doing even if they cannot do it in the way they would prefer. And, they’re just as important as anyone else.

Nathan is of immense assistance to Miss Sandy, despite not being able to walk.

“Nathan’s Wish” is one of only a handful of books written for children that feature a character with Cerebral Palsy, and it serves as a good example for all children – with or without a disability – about how to change a negative to a positive.

Among the colorful and engaging selection of children’s books, there are few characters with a disability that young people with Cerebral Palsy can relate to. However, as evidenced by Romeo Riley’s crack detective work and the photos of ballerinas in pink, that tide is slowly turning.