Internal mini form

Contact Us Today

The art of listening, and expecting others to hear what you have to say, sounds easy enough, but learning to do it in a way that makes others feel important and validated can be a challenge.

Lending an Ear

It’s a skill that most of us are born with; the one that allows us to function day to day, take direction, gather information, give directions, and make sense out of complex situations.

But truly listening to another person is about more than taking in information. It’s about considering the ramifications of what the other person has to say, and then, acting upon their concerns. It allows parents to bond with their children by knowing what is on their minds, understanding their state of mind, and assuring them of their importance and value as a member of their family, and their community.

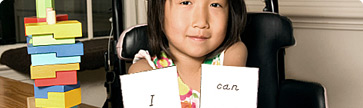

Parents of children with Cerebral Palsy interact with a number of individuals; doctors provide information and direction about a child’s condition, therapists tell parents and children what they will need to do to expand their capabilities, and teachers provide information about what a child is learning, and their educational outlook. But the most important information a parent will take in – or give – will be communicated between himself or herself and a child.

This is where a parent learns how their child is feeling. There’s nothing that is more important in the parent-child relationship than communication skills. If a parent is not truly listening to a child, they can misinterpret a situation in a way that will hurt a child’s feelings, or damage self-esteem. That in turn can create an environment where a child, chooses not to confide in a parent.

The good news is that if a parent is less than confident about their ability to listen with interest and clarity, or about their ability to be heard by their child, family members, or anyone else, there are some simple and helpful strategies that can be learned. Being a good listener – and expecting the same courtesy in return – is the ultimate test of the Golden Rule, and one that can, without fail, be mastered.

1. Practice “active listening”

Listen: Active listening is a process by which a person uses their entire body to participate in a conversation. This means that a parent should physically relax, nod, and demonstrate they are taking a conversation seriously. Gestures like turning and facing the child, placing the kitchen utensils side while cooking, moving away from the computer, closing the newspaper, or turning down the television allows the other to know you place importance on their conversation.

Be heard: It’s important not to let a child pout or become so emotional that a tantrum erupts. It’s important to acknowledge the child’s emotions, no matter how irrational, but to be firm in resolve where needed. Nobody is heard through power struggles so if one begins, gently let the child know that you will be back in a few minutes to discuss further, but you need to “put the clothes in the dryer.” This allows, the child to emotionally cool down. Have you heard the phrase, “My ears can’t hear you when you pout?” It works. Rewarding positive behavior, while downplaying negative means the child’s concerns will be addressed if there is respect while conversing.

2. Make eye contact

Listen: If a parent is looking elsewhere – instead of into their child’s eyes – it can be perceived as if the parent is not taking the conversation seriously. So, even if a parent’s concerns are stacking up, it would be best to make sure a child knows they have your full attention on topics that matter to your child.

Be heard: If a child is not facing their parent, or is not physically engaged in a conversation, he or she cannot fully absorb important information without distraction. Having patience, waiting until the child finishes the task they are involved in, and encouraging eye contact can enhance your child’s ability to hear your thoughts and concerns.

3. Repeat the message

Listen: One way to acknowledge the other in a conversation is to mirror, or repeat, what they have said in your reply back to them. For example, “I feel bad that your feelings are hurt, perhaps…” Another option involves waiting until the end of the conversation, repeating the main points and resolve, and assuring the child that their thoughts, opinions and contributions matter.

Be heard: If a parent suspects their child – or anyone else for that matter – has not processed what has been said, or how he or she feels about a situation, they should not hesitate to ask the child to repeat their statements. This way, the parent can assess the seriousness in which the other party in the conversation is taking the subject matter. Once statement is repeated, you can ask for the child’s thoughts while acknowledging their reaction. For example, if they repeat your statement with a bit of attitude, you can defuse the conversation by asking “What are your thoughts on that as I see you are not totally thrilled with the suggestion?” It allows them to express their feelings and ideas on the subject. When both sides air their concerns, it is easier for both parties to accept compromise.

4. Don’t minimize concerns

Listen: It’s easy to feel like a child’s concerns are not as important as those of a parent. But a child has emotions, thoughts, and feelings like anyone else, no matter how old he or she is. And, as a child with a disability, they may struggle with their ability to communicate so they try to make their words count when expressed. An ill-advised comment, such as “don’t be silly,” “this won’t matter in the long run,” or, “ignore them, and they’ll go away,” can unintentionally come across as flippant or uncaring.

Be heard: The converse of this also holds true. Because a parent is older, children can sometimes dismiss parent concerns as outdated. The child may just assume that a parent doesn’t understand their predicament. The parent should let the child know their point of view is understood, but also be absolutely clear regarding why a decision has been made. By learning to “pick your battles” parents can use restraint in using the “power card” for those items that really matter.

5. Don’t interrupt

Listen: As tempting as it may be to interrupt a child – especially if the parent strongly disagrees with what they child is saying – it’s best to wait until the child has aired their grievances in full. Interrupting the other person has a way of leading to angry pronouncements and hurt feelings, which are contrary to what you’re trying to achieve.

Be heard: Likewise, a parent has the right to expect not to be interrupted. If the child does interrupt, it’s okay to politely ask them to not interrupt until you have finished your point. Often when a parent is conversing on the phone or with others, a child may try to gain the parent’s attention. Gently signaling with the index finger to wait a moment when used consistently will serve as a reminder to the child that you will divert your attention to them as soon as you are free to do so. When free, privately taking the child to the side to remind them not to interrupt while you are in conversation with others (unless there’s a dire emergency), and then providing undivided attention to their issue sets a consistent message.

6. Ask for help

Listen: Sometimes, as an able-bodied parent, and someone that is more mature than their children, it can be hard to relate to your child’s concerns. If a parent doesn’t understand a child’s concern, they should ask them to elaborate. Signs of frustration, desperation, or heavy emotion means the child is very affected. A sympathetic and caring parent response opens dialogue to better understanding.

Be heard: The parent has to be willing to do the same though – even if they feel their word should be the law. Sometimes, a child just can’t get their arms around adult concerns. It would benefit a parent to explain further. A child with disability likely already feels their situation is beyond their control, and they need to understand that there’s rhyme and reason behind the decisions made as a parent, especially if the decision seems punitive. It is helpful to remember that situations like these are teaching moments. The way you behave will likely be mirrored by your children in time.

7. Try not to get emotional

Listen: Getting emotional by getting upset or angry at a child is sometimes unavoidable, but should be restrained, if at all possible. Being emotional can make it much more difficult for a child to comprehend. The child is likely to remember, and react to, the anger and gestures more so than the message being conveyed. Power struggles are born from emotional outbursts. Some authorities in behavior modification suggest that the parent respond to the child with the same respect and tact the parent would like to receive in return, or that would be used with an acquaintance, co-worker or boss.

Be heard: This can be a thorny one for parents to navigate with their child. A parent wants to know how a child feels, and wants to let the child express emotions. The key is to direct a child’s frustration in a manner that is respectful. Modeling respectful behavior is your first line of defense as children learn by their parent’s interactions. Letting the child have space when in full blown tantrum can be helpful. Not allowing the child to throw, hurt or verbally assault another is important and should be monitored consistently. It may be helpful to remember that a child that seeks negative attention, likely tried positive without success. Paying attention to a child early on may thwart disrespectful outbursts later.

8. Find a quiet place

Listen: If there is loud music playing, a television set in the background, or several people in the room, it’s not likely going to be the best environment for a heart-to-heart talk. Find a nice, quiet and appropriate place to listen to your child.

Be heard: The child must also make an environment suitable. Ask them to put aside their hand-held devices, iPods, computers, phones and other distractions. If you would like to be heard, you may have to wait until their conversations with others have concluded. It is helpful not to assume that they are instantly ready to receive your messages at every whim. “John, do you have a minute?” and “Susie when you get a moment can you come see me, I’d like to talk to you about…” will allow the child to refocus, end their tasks and be more receptive to your thoughts.

9. Show support – even if you disagree

Listen: A common dispute between children with disabilities and the parent is when, or if, a child will be able to take part in a given activity. It’s important to listen to a child’s point of view because it can provide the parent with vital information about a child’s aspirations not otherwise known. The child may say “Can I go to John’s birthday party? Everyone is going.” A parent may, at first impulse want to say “Just because everyone is going, doesn’t mean you have to.” A more appropriate response would be, “I didn’t know you knew John. Why is this party so important to you?” This type of reflection acknowledges the request and seeks to find out why being involved is important. It may lead to other viable options to consider, or a way to compromise. It also becomes a valuable “sharing moment” where the child may become more comfortable conversing with the parent over time.

Be heard: If a 12-year-old child goes to a parent to seek permission to participate in bungee jumping, the idea will likely be nixed by the parent. Seek to understand why this activity interests them. But it’s not enough to just say no. Tell the child that one day, he or she very well might take part in such an activity, and explain why doing so at their age is inappropriate. Coming to a compromise by agreeing to someday view a bungee jump and talk to instructors may suffice while leading to a teachable moment and fun parent-child excursion.

10. Remember, you’re the parent

Listen: Children with disabilities often feel as though they are not in control of their lives. Sometimes, when a parent and child have a conflict, a child will see it as the parent forcing his or her will on them. Parents should seek a balance between limiting a child and empowering them. That point is different for all children.

Be heard: Mom and dad set the tone for their relationship with their child. A parent deserves respect, as does the child. A child should be aware that not heeding their parents’ directions will have consequences. Clear and effective communication between parents – much of which is listening – will in most cases diffuse difficult situations. Diffusing power struggles ensures that troubled conversation doesn’t lead to resentment and unpleasant attitudes.

Healthy habits can enhance emotions and communication. Healthy diets, physical exercise and proper sleep habits can contribute to less individual and household stress. Boredom in children can lead to discontent, so encouraging activity, hobbies and interests may prove helpful. Devoting and genuinely enjoying one-on-one time together can build stronger relationships that are better able to weather disputes. Respect, validation and patience can help a person listen, converse and be heard.

Inspirational Messages

A message can be verbal, or something that’s felt in the heart. What all messages have in common is that they can influence our perspectives for better or worse. Luckily, by gathering positive messages, the bad ones can be cast away.

- Accept Help

- Advocate

- Celebrate Your Child

- Dare to Dream

- Experience Magic

- Find and Foster Creativity

- Gain Perspective

- Get Your Mojo Back

- Keep the Family Together

- Let Go

- Listen

- Love without Barriers

- Pat Yourself on the Back

- Persist

- Plan Ahead

- Pursue Happiness

- Reinvent Normal

- Share Some Love

- Take a Break

- Welcome to Holland